Recession Not Over for Poor: Families Stretch Food to Last

After Jaime Grimes found out in January that her monthly food stamps would be cut again, this time by $40, the single mother of four broke down into sobs — then she took action.

The former high school teacher made a plan to stretch her family’s meager food stores even further. She used oatmeal and ground beans as filler in meatloaf and tacos. She watered down juice and low-fat milk to make it last longer. And she limited herself to one meal a day so her kids — ages 3, 4, 13, and 16 — would have enough to eat.

“I just want my kids to be fed," said Grimes, 38, of Lincoln, Neb., who suffers from chronic back problems, arthritis and muscle pain that make it difficult for her to stand. She is applying for disability but in the meantime has $950 a month — $500 in child support and $450 in food stamps — to feed and house her family. "I just want my kids to have the basics of life that, unfortunately, I can't give them right now," she added.

Grimes and her children are among the estimated 49 million Americans who have limited — or uncertain — access to enough food to meet their daily needs. The numbers of people living in such hardship initially spiked during the Great Recession to around 15 percent of Americans, and has hovered there, failing to return to pre-recession figures of 11- to 12-percent though the economic slump ended nearly five years ago in June 2009, according to a new report by Feeding America, a national hunger relief charity.

BRIAN LEHMANN / FOR NBC NEWS

BRIAN LEHMANN / FOR NBC NEWS

“Nothing is getting better,” said Craig Gundersen, lead researcher of the report, “Map the Meal Gap 2014,” and an expert in food insecurity and food aid programs.

“Let’s stop talking about the end of the Great Recession until we can make sure that we get food insecurity rates down to a more reasonable level,” he added. “We’re still in the throes of the Great Recession, from my perspective.”

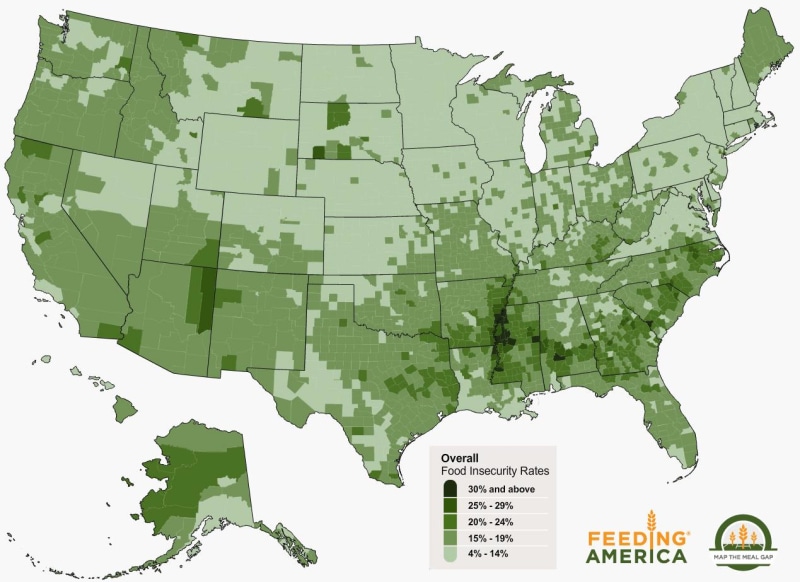

The report quantifies people's ability to buy or access food, including whether through charity or government aid, in the nation’s 3,143 counties — which all have individuals like Grimes struggling to put meals on the table. Using 2012 data — the most recent available — from various federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Census Bureau and the Agriculture Department, some of the key findings were:

- Counties with the highest rates of food insecurity were more likely to be in rural areas than in metropolitan regions;

- Eighteen counties in the top 10 percent for highest food-insecurity rates and highest cost per meal have more than 20 percent of their population living in hunger;

- Minorities are facing serious hunger issues. Ninety-three percent of counties with a majority African-American population fall within the top 10 percent of food-insecure counties, while 60 percent of majority American Indian counties fall in that category;

- The state with the highest rate of food insecurity is Mississippi at 22.3 percent, while New Mexico has the highest rate of child food insecurity at 29 percent;

- Low-income Americans said they needed to spend 10 percent more dollars a week in 2012 than in 2011 to provide their families three meals a day.

The emerging hunger problem is “startling” and “extreme,” said Jeremy Everett, director of Baylor University’s Texas Hunger Initiative, which uses Feeding America’s data to pinpoint areas facing food challenges statewide.

“The recession has subsided for most Americans but it still hasn’t subsided for low-income Americans. Their situation just has not improved,” he said, adding that it was “probably worse now” because a temporary funding boost in 2009 to the key government food aid program known as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) was allowed to lapse by Congress last year.

“It seems like we are stacking the deck against” low-income people, said Everett, who was recently named to the congressional National Commission on Hunger. “We’re missing rungs at the bottom of the (economic) ladder to be able to help people to get to the top.”

COURTESY OF FEEDING AMERICA

COURTESY OF FEEDING AMERICA

Feeding America’s data was pretty consistent with figures that advocates have seen in recent years after the recession began, including figures released by the Agriculture Department last fall, said Christine Ashley, a policy analyst at Bread for the World, an anti-hunger advocacy group.

“We haven’t really seen increases in food insecurity (since the recession) which is a good thing,” she said. “The downside of that is there are still way too many food insecure people.”

One number that struck her in the report, though, was that nearly 30 percent of the people facing hunger issues were working — and their incomes put them just above the threshold to qualify for federal food aid.

“They’re clearly working low-wage jobs and aren’t able to make ends meet,” Ashley said. It helps to understand “why we have such a problem with food insecurity despite lower unemployment rates,” she added.

“We’re a good family. We’re poor, but that doesn’t stop us.”

Gundersen said some of the factors keeping many Americans in food trouble could be that the economic recovery was anemic and the recession was having a lingering impact. Everett, of the Texas group, said if more — and better — economic opportunities weren’t soon provided, the level of Americans living in such food difficulties “will be the new norm.”

For the Grimes family, the national economic issues have taken their toll: they were hit by the government’s cut last year to food stamps (which were reduced yet again, to $50 overall, when Grimes got more child support. She only gets child support for two of her children).

Grimes landed in poverty, she said, after she left her husband three years ago because of irreconcilable problems in their relationship.

She and her kids live in an apartment without amenities many people enjoy, like Internet, cable or a television. Grimes goes to every food pantry she can and only buys food on sale. Her oldest two children — Maggie, 16, and Kevin, 13 — collect backpacks of donated food from school each Friday. If they don’t get the bags, “there isn’t going to be enough food,” Maggie said.

BRIAN LEHMANN / FOR NBC NEWS

BRIAN LEHMANN / FOR NBC NEWS

No comments:

Post a Comment